ATSC 3.0 Chases ‘Cloud-First’ Cars

Just three years after broadcasters and technology vendors first gathered in Detroit to pitch the automotive industry on the datacasting capabilities of the ATSC 3.0 next-generation TV standard, the industry returned last week to describe the significant progress made in bringing 3.0 reception to cars for information, safety and entertainment applications, perhaps as soon as next year.

The Advanced Television System Committee (ATSC) held its annual “NextGen Broadcast Conference” last Wednesday and Thursday in Detroit, where the “Next-Gen TV Auto Symposium,” organized by broadcast consortium Pearl TV and hosted by Scripps-owned WXYZ, was held back in May 2019. At that event broadcasters unveiled plans to launch a test bed for automotive applications using the 3.0 spectrum, which they touted as a cheaper and more reliable way to deliver data such as software updates to automobiles. And they invited car makers and automotive parts suppliers to participate in hands-on development.

Since launching in December 2020, the “Motown 3.0 Open Test Track” has been busy providing high-powered 3.0 broadcasts from Scripps’ Detroit independent WMYD, which in partnership with Graham Media, CBS and Fox has set aside 10% of its overall capacity for the automotive industry’s use. The “Test Track” initiative in Detroit has been bolstered by other 3.0 automotive field trials in Phoenix; Santa Barbara, Calif.; and Portland, Ore., as well as a 3.0 testbed on Jeju Island in South Korea, with strong reception results widely reported.

To that point, ATSC President Madeleine Noland announced Thursday in Detroit that Korean automotive parts supplier Hyundai MOBIS has already developed an ATSC 3.0 receiver for vehicles, completed testing and plans to deliver the solution to automakers.

“In fact, they anticipate the first commercially available automobile equipped with 3.0 to be available in the U.S. market next year, 2023,” Noland said.

New Field Test Results

No other big automotive product announcements were made at the NextGen conference, but there were new, detailed 3.0 field test results shared from both Detroit and Portland as well as presentations on other datacasting applications like distance learning and emergency alerting.

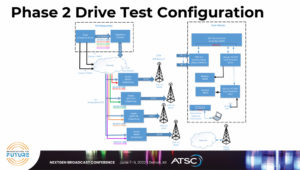

Coast-to-coast test configuration

The most notable new data came from a “Coast-to-Coast” road test spanning the width of Michigan and using signals from WMYD as well as low-power stations WKAR Lansing (Michigan State University) and WXSP and WOLP Grand Rapids (Nexstar).

The Coast-to-Coast test involved the delivery of both data files and streaming 720p video and audio to Sony 3.0 receivers in vehicles traveling at highway speeds. That included “handoffs” between different transmitters operating in a multiple frequency network (MFN), where different channels are used to transmit the same content across a wide geographic area.

Merrill Weiss, the consulting engineer on the test, said that 3.0 reception worked as expected, including a few areas of signal dropout along the route that were predicted by two established propagation models and could be solved for data delivery by appropriate buffering.

He said the test team, which included executives and engineers from Scripps, Sony and Heartland Media, was able to prove the reliable reception of data as well as HD programming on the road. That included the error-free delivery of a 7.6 GB file to a moving vehicle at highway speeds without the use of a return channel or a data carousel, as well as uninterrupted reception of 720p HD programming.

“We delivered HD video with seamless switching between multiple transmitters as we were driving between different sites down I-96,” Weiss said.

The test explored the use of new forward-error-correction (FEC) techniques, including the KenCast Fazzt FEC from Alchemedia SG, and new algorithms for reception from multiple antennas (diversity antenna reception). It also used a technique for non-realtime file delivery called bandwidth multiplication, which involves sending independent feeds that were coded differently from the source server to each transmitter individually. The FEC can then put together the individual feeds to construct the complete file.

“They were centrally processed and allowed to contribute data to the overall file reception from two different transmitters at the same time,” Weiss said. “So, it effectively took our 1 Mbps bandwidth and doubled it to 2 Mbps and allowed us to capture the files that were being received and downloaded at twice the speed we could have otherwise.”

Auton, a manufacturer of telematics control units (TCUs) for automobiles, successfully tested 3.0 reception in automobiles in Portland in 2021 with low-power KORS. Though the signal from the 15-kilowatt transmitter was receivable at a range of up to 40 miles, the company identified several areas that could benefit from 100–200-watt gap fillers.

Auton’s 3.0 test route

Auton came to Detroit for further trials of its prototype 3.0 TCU this past March, using “two-level” forward-error correction: application-layer FEC that works over a longer time frame to address packet loss; and physical layer FEC that works over a shorter time frame to address bit errors. Robert Foster, president and CEO of Auton, said he was very impressed with the performance of WMYD’s 930-kW 3.0 transmitter, including solid reception across downtown Detroit and even inside tunnels.

“It was awesome to see it work,” Foster said. “The signal is so complete and uniform it’s impossible to hide from it. But we did our best.”

Auton did identify a problem area west of Ann Arbor, about 35 miles from the transmitter. But those problems, which included picture artifacts and browser refreshes, were mostly solved by tweaking the FEC. Foster has broad experience with cellular and satellite paths to the car and said that 3.0 is very accessible and cost-effective by comparison. He invited interested parties to come work with Auton for further testing on the “Oregon Test Network,” a network of six low-power 3.0 stations with which he has partnered. The stations have no existing commercial traffic to compete with and partners will have complete control of the waveform for testing.

“We need to move ahead,” Foster said. “The core technologies are there. It’s time to build it.”

A Cloud-First Proposition

The time appears to be ripe for broadcasters to pursue the automotive market according to a wide-ranging presentation by Roger Lanctot, director of the global automotive practice for Strategy Analytics. Lanctot noted that it is difficult to buy a car today that doesn’t have some sort of built-in wireless connectivity. But only electric vehicle (EV) manufacturer Tesla has created viable recurring revenues from that connectivity with its $10-per-month software updates constantly delivering incremental improvements to owners.

“The industry is still coming to terms with what is that value proposition for the consumer, and what is the consumer willing to pay for it?” Lanctot said. “Tesla is the only company that has figured this out.”

That could change with increased 5G deployment, which is “coming very fast on the network side,” Lanctot said. He forecast that shipments of 5G TCUs for cars will have a compound annual growth rate of 94% between 2021 and 2027, with volumes increasing from 322,000 in 2021 to 17.1 million by 2027.

L-r: John Lawson of AWARN, Mark Corl of Triveni, Luke Fay of Sony, Dr. Jong Kim of LG Electronics, Anne Schelle of Pearl TV

Connected-car initiatives were slowed in recent years in both the U.S. and Europe over spectrum allocations, including the FCC’s decision to free up a large chunk of DSRC (Dedicated Short Range Communications) spectrum originally reserved for automotive use. But safety concerns are driving new government-mandated features that are dependent on connectivity, such as “intelligent speed assistants” that warn drivers when they are going over the speed limit. So are new navigation and driver-assist tools like Cadillac’s “Super Cruise” hands-free driving system.

Lanctot said that “everything is driving towards a cloud-first proposition when it comes to driving a car, and all of the applications, whether they’re infotainment-, communication- or safety-related.”

That said, all of these new safety features bear significant cost implications for automobile manufacturers. And while they have partnered to bring connectivity to cars, car makers and wireless carriers have never seen eye-to-eye and still have what Lanctot describes as a “fraught” relationship. He said 3.0 could be seen as an attractive solution.

“If you’re an automotive engineer, connectivity is a necessary evil, wireless carriers are a necessary evil, and I am really interested in alternatives to cellular connectivity to my cars,” he said. “So, I’m not surprised to hear that we have a car with ATSC 3.0 arriving as soon as we just heard.”

Comments (0)