Sharpening Remote Production, Cloud-Based Workflows For The Long Haul

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 forced broadcasters to remove most personnel from their facilities and rapidly shift to new remote production techniques and cloud-based workflows. Two-and-a-half years later, the COVID-19 situation in the U.S. has stabilized, but many remote workflows still persist due to gains in efficiency and flexibility for both operations and staff. And advances in IP connectivity and public cloud technology are spurring further innovation, according to news and sports production experts who gathered last week for the TVNewsCheck webinar Remote Production: Optimizing Technology and Workflows, moderated by this reporter.

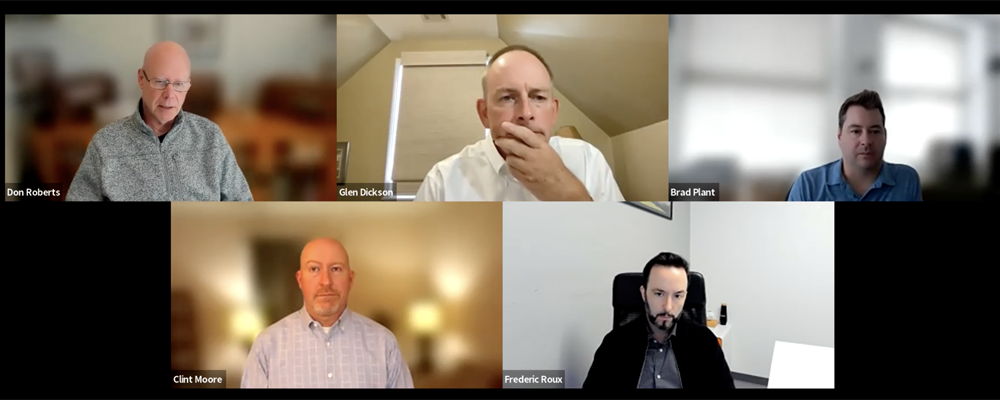

Sinclair’s Cloud Control

During the pandemic Sinclair Broadcast Group implemented a new workflow for sports production called “Cloud Control” that it developed with its mobile truck vendor, Mobile TV Group. The new scheme was designed to “essentially remote some of the functionalities from remote trucks during [professional] games back to the studios and the regions that are televising them,” said Don Roberts, Sinclair SVP of sports engineering and production systems.

Don Roberts

With Cloud Control, there are five to six people at the RSN that Sinclair doesn’t send to the game, including a director, producer, replay operator and a couple of graphics operators. Those personnel stay home and are able, via an IP connection, to remotely control devices in the truck and see their camera feeds on a multiviewer back at the studio. (Sinclair has successfully used both JPEG-2000 XS compression as well as SRT for video backhauls.)

“The key to that is low latency,” Roberts said. “We’ve tried a couple different variations of that over the course of the last two years, and we have it now in a place where we make it work pretty well.”

Sinclair has installed Cloud Control rooms in most of its RSNs at this point, and now is looking at adding more remote capability to allow an RSN to handle multiple games per day. But the RSNs haven’t expanded their use of remote production much beyond Cloud Control. Now that the COVID-19 situation has improved, they are back to sending large production teams to cover MLB games. If teams from two RSNs are playing each other, Roberts said, there may be as many as 60 production personnel onsite.

A new remote production venture for Sinclair is underway at Tennis Channel, which a few months ago began covering the fast-growing racquet sport of pickleball. Tennis Channel has already covered about five or six pickleball tournaments at various locations across the U.S. Not all of the coverage airs on Tennis Channel, with some of it going to other networks or streaming platforms.

The production team at Tennis Channel headquarters in Santa Monica, Calif., has developed a workflow where it sends two or three people to pickleball venue and sets up a mix of manned, pan/tilt/zoom and POV cameras, including autotracking cameras and LiDAR technology. Everything else is done remotely, including switching of cameras, graphics and replay.

“We’re literally doing an eight or nine-camera completely remote, with the exception of two camera operators,” Roberts said.

How transmission is handled depends on what type of connectivity exists at the venue, with four or five different scenarios ranging from traditional fiber links to bonded cellular systems.

Tennis Channel has about five more pickleball events to cover in 2022 including stops in Las Vegas, Washington, and Orlando, Fla. Sinclair is considering building a small production trailer, perhaps 20 feet long, that can be towed by a pickup truck and used to haul the pickleball production gear around. Staying small is key for pickleball, which is often held at compact venues that can’t accommodate the large mobile trucks traditionally used for professional sports coverage.

“What we’ve learned is that if we can do things remotely — not necessarily the cloud, but just remote production — we’re going to do that,” Roberts said. “We’re huge fans of that. And our Tennis [Channel] people are in the forefront of doing not just pickleball, but tennis tournaments all over the world, remotely. We’re sending now a fraction of the production people we used to send to tennis events.”

For WLS, Connectivity Remains Challenging

ABC O&O WLS Chicago was fortunate during the pandemic to have ample space to allow for social distancing of personnel in the building, so day-to-day news production “wasn’t a huge hurdle,” said Brad Plant, executive director of technology for the station. WLS also does an extensive amount of non-news remote production in its market, with a dozen community events a year including parades, auto shows and festivals. All of those are live event productions similar to sports.

Along with spurring the adoption of new technologies, the pandemic has made viewers more accepting of new production styles, Plant said.

Brad Plant

“I think the pandemic has changed the way that we, as content creators, and our viewers look at news and sports production,” he said. “There are more acceptable production techniques like Zoom, and similar products, that may not have been looked at prepandemic. We’re trying to look at new technologies out there that allow us to bring people together not just for collaboration, but for production, and see how far we can push them as we [go] past this pandemic era.”

WLS’s goal is to use technology that is as flexible as possible with several options for connectivity, which remains the biggest challenge for remote production. Covering a parade is far different that rolling up to a sports venue like Wrigley Field that has ample fiber connectivity.

“Every event we do we have to be able to pivot to the type of event, the demands that the production team needs, and especially our connectivity, which is the big thing,” Plant said.

The station is in the midst of building a 20-foot mobile production trailer that will be able to support a wide range of production techniques. It will be able to do a traditional remote model with a full production team including a TD and director where everything is produced onsite, and the program feed is streamed back to the station via fiber, microwave, satellite or bonded connection. A second option is a full REMI model where all the camera feeds are brought back to the station and the show is produced there.

But the challenge there is bandwidth and connectivity, Plant said.

“Can we get eight camera feeds back to our station reliably and with low latency, and give that director the same experience they would otherwise have with an on-site production?”

A third option is a hybrid model, where the gear is located onsite in the production trailer but is being remotely controlled from the station, including switching between camera feeds. Latency is also a big factor there, both for viewing the video as well as communicating to staff in the field.

“You’ve got to have low latency for communicating to the production staff in the field while the director and producer sit back at the station,” Plant said.

The Starlink LEO (low Earth orbit) satellite service isn’t available yet in the Chicago market, but Plant thinks that it has great promise for supporting such low-latency communications. However, he doesn’t see it as an option for video transfer from the field due to its relatively low upload capacity.

While WLS make use of bonded cellular connectivity for newsgathering when possible, big events like parades with thousands of cellphone users competing for bandwidth sometimes make that untenable for long-form live production.

“We still heavily rely on microwave, and we’re fortunate to have a large microwave infrastructure here in the city,” Plant said.

Gray Refines Its Work From Home Game

With the improvements in the COVID-19 situation, Gray Television stations have brought many of their employees back to the building, said Clint Moore, director of broadcast operations for Gray, but they still have remote production options available.

Clint Moore

Many pieces of remote production technology that Gray relied on through the pandemic had actually been in place for years beforehand, Moore said, “but we never really got around to testing it.” The onset of the pandemic forced the issue, and in three to five days Gray went from stations full of people to “very skeleton staffs,” with producers, directors, anchors and even master control operators working from home.

Happily, the IP-based systems that Gray had put in place worked well and personnel were quick to adapt, including some getting a quick education in the fine points of home broadband service. While most staffers have returned to their seats at the stations, some personnel have continued in a 100% work-from-home, remote model.

“They’re assigned different duties, different regions, they get up and are scheduled and they know what they’re supposed to do for the day,” Moore said. “And they’re able to remote in from home and help those stations out, in case there are sick calls or somebody is short-staffed.”

Moore feels like the group is well prepared for future crises such as COVID-19. On that note, in the past week Gray provided remote production assistance to several stations impacted by Hurricane Ian.

Gray is continuing to invest in new technology that makes it seamless to work either at the station or from home. That includes buying new laptops and replacing traditional dual monitors in the newsroom with a single, large monitor with a docking port for a laptop, a compact combination that also works well in a home environment.

“When you try to come up with a remote workflow for an employee from their home, some folks don’t have a lot of room,” Moore said. “So, you’ve got make sure that the equipment we’re going to roll into their home is going to work properly, and it’s not going to take up their whole living area or bedroom or kitchen.”

For Dalet, Lure Of The Public Cloud

COVID-19 accelerated broadcasters’ adoption of public cloud technology for production by four to five years, said Frederic Roux, SVP of worldwide enterprise sales for Dalet. He added that using the cloud to provide tools to a remote workforce can be a more cost-effective solution than investing in a virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI).

Frederic Roux

“At Dalet, we’ve always been a big proponent of leveraging cloud, specifically for news and sports,” Roux said. “A lot of that relates to scaling production cycles. Depending on where you are, you need more or less people producing, you have big events, it makes sense to have on the back end an infrastructure that auto-scales with your needs.”

Dalet was already in the process of shifting its software products to cloud technology and web-based applications, and the pandemic sped up that development as well. The company has released a whole new generation of Web-based tools for news production and collaboration called Pyramid.

The concept of Pyramid, Roux said, “is really your laptop as your desktop, being able to do your ingest, your edit, your news planning, your playout from a Web-based interface. To get away a little bit from heavy investments in a VDI infrastructure and the like.”

Pyramid is designed to work on either public or private cloud platforms, and Roux said Dalet has several customers interested in running the software in their own data centers. He noted that the economics of the public cloud can vary widely depending on a broadcaster’s size, and said private cloud is still “a very attractive opportunity for people who can achieve centralization of resources” such as large media companies with diverse businesses beyond news.

“So that if you have to serve 20, 30 or 200 local stations, you can work with one central system, one central facility, as opposed to deploying multiple systems all around the U.S.,” Roux said. “So, I think there is cross-pollination between the need for remote production and the attraction of the public cloud to enable a lot of auto-scaling. But moving to public cloud, for a company like us, opens a lot more avenues in terms of hosting a system to create a true centralized production hub, that can serve a user at home or a user in a different location.”

Comments (0)